Very recently a video of a captive cheetah has rapidly spread on the web, in which apparently the owner is talking with the animal in Farsi. The Iranian Cheetah Society is investigating the originality of the video and has tried to contact the video creator. It is not understood if the video is actually captured in Iran, or in one of the Persian Gulf countries where keeping exotic animals like cheetahs are common, and if the animal in this video is an Asiatic cheetah. It is not possible to draw any firm conclusion based on this video as Asiatic and African cheetahs are morphologically are almost look alike. The Iranian Cheetah Society encourages the public to contact us with any information about this video at: [email protected]

Cheetah

The new issue of the Society’s newsletter has just been released. Our top stories feature news from ICS’ cheetah monitoring project, top camera trap prizes won by ICS in late 2014 and early 2015, successful capture of a dog-eating leopard, and education activities in different parts of the country.

Download the newsletter here.

It’s still possible to save the Asiatic cheetah, the world’s second-rarest cat

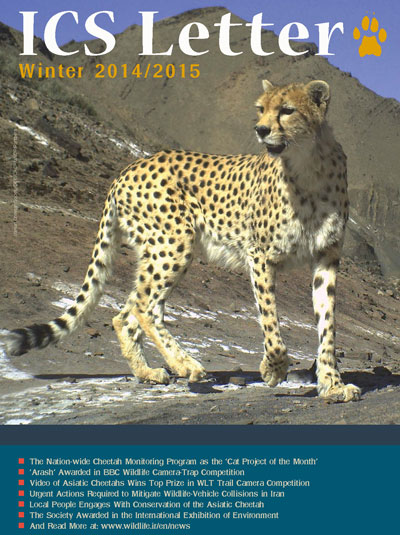

The Conservation: The last few surviving Asiatic cheetahs live in Iran, where they stalk the hyper-arid landscape, where temperatures swing from -30°C to 50°C. This is the only place in the world a cheetah, most of which live in Africa, will experience snow.

Iran is home to the last known population of Asiatic cheetah, a creature which once roamed across vast ranges of west and south Asian countries, from the Middle East to India. Today, the cheetahs are known only from around 15 reserves in Iran, all officially protected by the country’s government.

Together with genetic distinctiveness from their African cousins, the Asiatic cheetahs are smaller and more slightly built. Iranian biologists were surprised to learn that the Asiatic cheetahs are mainly found in mountainous regions – a very different proposition from the view expected from wildlife documentaries in which cheetahs pursue sprinting gazelles across open plains.

Camera traps are reliable tools to try to gauge the population of these spotted cats, whose markings are individually unique. However, this technology has been rarely applied to cheetahs across their global range due to the paucity of individuals and their elusive nature. Due to political sanctions, the necessary equipment is not easily available in Iran, and this has prevented a thorough assessment of the species in the past.

Thanks to various donors and partners, including Panthera and Dutch NGO Stichting SPOTS, a monitoring program was recently launched that would fill the gaps in our knowledge about the cheetah that is essential for its protection. Even so the results were surprising, revealing only 40 to 70 cheetahs across the country – smaller even than previous estimates of up to 100. Listed as critically endangered by the IUCN, the Asiatic cheetah is among the rarest cats in the world at subspecies level, after the Amur leopard.

Guarding Iran’s last cheetahs

Around 125 game guards protect the cheetah’s range in Iran as Cheetah Guardians, thanks to tremendous efforts of the Conservation of Asiatic Cheetah Project (CACP), the Iranian Department of the Environment (DoE), and UNDP in Iran, which tried to double the number of guards employed by the DoE during the past decade. Equipped with 4WD vehicles and motorbikes, each guard is responsible for protecting around 640km2 of the landscape, an indication that more forces are needed.

In order to safeguard the cheetahs, the DoE established more reserves while existing reserves received more resources. In the Iran’s northeast Miandasht Wildlife Refuge has been a key site for the cheetahs after a threefold boom in prey species. As a result, the cheetahs have established a breeding population there, vital to help re-colonise other reserves.

As is the case for many wildlife species, the cheetah was little known among the public ten years ago. But with the animals’ plight appealing to the media it has garnered considerable coverage, leaving the public in no doubt about the state of the cheetah’s decline. With united effort from government and NGOs, this year the cheetah even became the first species to appear emblazoned on the Iranian national football team’s jerseyduring the 2014 World Cup in Brazil.

So as a symbol of the nation’s wildlife, the public awareness and support the cheetah receives is an important step to ensure its long-term survival. But it is not enough. It is vital to build an expert opinion on what to do about the species’ critically small population, rising mortality from human causes, such as traffic collisions, and falling birth rates.

While further research is needed, we know that Asiatic cheetahs have much lower genetic diversity than African cheetahs, but we are still hopeful that better connectivity between the various reserves to allow cheetahs to intermingle could maintain a basic level of gene flow between small cheetah populations.

We need the authorities to confront and defeat plans for property development and infrastructure such as roads, mines and railways within the main cheetah reserves. For example, a road to be constructed through Bafq Protected Area in central Iran was a major concern, but the DoE managed to stop construction and propose an alternative route.

Cheetahs are known to kill small livestock, and claims of cheetahs killing young camel, sheep, and goat are rife among shepherds. Recent cases in different parts of the country have raised concerns that cheetahs could be killed by protective herders. At least five have been known to be killed by herders since 2010, twice the number killed in the previous decade. To try to prevent this, the Iranian Department of Environment and CACP established a programme to compensate for cheetah predation for five years.

On August 31 1994 a cheetah was rescued from dying of thirst in central Iran. Named Marita, for nearly ten years she was the only evidence of the existence of cheetahs outside Africa. In 2007, the Iranian Cheetah Society (ICS) designated August 31 as National Cheetah Day, an annual event to draw people’s attention to conservation issues in Iran. The cheetah is lucky to have a day bearing its name, but to survive they will need much more than luck.

Khosh-Yeilagh is one of the most well-known protected areas located north of Shahrood in Semnan province. For more than four decades, the area has been a historical habitat for the Iranian Cheetah with an initial estimated 50 to 70 cheetahs living in the area in the 1970’s.

For years it was believed that the Iranian Cheetah has become extinct in Khosh-Yeilagh with the last sighting going back to 1983. However, a recent sighting made by the Park Ranger, Mr Ajami, provided hope that cheetahs may still exist there. This was later confirmed again by the Rangers when two cheetahs were sighted.

Subsequently, the Environmental Protection Department of Semnan province started a monitoring project in cooperation with the Iranian Cheetah Society. The objective of the program was initially to observe the conditions of cheetahs in the area and to obtain more information about the rare Iranian cat. The project was started last winter and in the first phase several cameras were installed at locations specified by the park rangers and environmental experts.

The Iranian Cheetah Society has undertaken projects in the past to educate the residents of the near-by villages about cheetahs. As part of the project, art festivals and educational plays have been organised to familiarize residents with cheetah habits and behavior.

Iran is rushing to try to save one of the world’s critically endangered species, the Asiatic cheetah

AP Photo/Vahid Salemi

TEHRAN, Iran (AP) — Iran is rushing to try to save one of the world’s critically endangered species, the Asiatic cheetah, and bring it back from the verge of extinction in its last remaining refuge.

The Asiatic cheetah, an equally fast cousin of the African cat, once ranged from the Red Sea to India, but its numbers shrunk over the past century to the point that it is now hanging on by a thin thread – an estimated 50 to 70 animals remaining in Iran, mostly in the east of the country. That’s down from as many as 400 in the 1990s, its numbers plummeting due to poaching, the hunting of its main prey – gazelles – and encroachment on its habitat.

Cheetahs have been hit by cars and killed in fights with sheep dogs, since shepherds have permits to graze their flocks in areas where the cheetahs live, said Hossein Harati, the local head of the environmental department and park rangers at the Miandasht Wildlife Refuge in northeastern Iran.

At the reserve, rangers are caring for a male cheetah named Koushki, rescued by a local resident who bought it as a cub from a hunter who killed its mother around seven years ago, said Morteza Eslami Dehkordi, the director of Iranian Cheetah Society. “Since he was interested in environment protection, he bought the cub from him and handed it to the Department of Environment,” he said. The cheetah was named after his rescuer’s family name.

With help from the United Nations, the Iranian government has stepped up efforts to rescue the species – also with an eye to the potential for tourism to see the rare cat.

Rangers have been equipped with night vision goggles and cameras have been set up around cheetah habitats to watch for any threat. They have also been fitting cheetahs with U.N.-supplied GPS collars so their movements can be tracked. Authorities built shelters in arid areas where the cats can have access to water. They’ve also reached out to nearby communities, training them how to deal with cheetahs and promising compensation for livestock killed by cheetahs to prevent shepherds or farmers from hunting them.

Also, any development projects in cheetah habitats must be approved by Iran’s Environmental Department.

The efforts were given a symbolic boost at the ongoing World Cup in Brazil, where Iran’s team wore images of the cheetah on their uniform. The country has also named August 31 as Iran’s National Cheetah Day since 2006.

Once known as “hunting leopards,” Asiatic cheetahs were traditionally trained for emperors and kings in Iran and India to hunt gazelles. They disappeared across the Middle East about 100 years ago, although there were sightings in Saudi Arabia until the 1950s. They vanished in India in 1947 and ranged in Central Asia as far as Kazakhstan up to the 1980s.

Gary Lewis, with the U.N. Development Program, said the dropping numbers in Iran are alarming.

“There are no other Asiatic cheetahs like the one that you have here in Iran, so it is essential for us as human beings to conserve our biodiversity by protecting this animal,” he said.

Iran also hopes to attract more foreign tourists under moderate President Hassan Rouhani, who has vowed outreach to the West.

“It is an endangered species. The cheetah is considered to be one of the most charismatic cats,” said Vice President Masoumeh Ebtekar, who heads Iran’s Department of the Environment.

“It is important for, for example, our ecotourism when many people who enjoy coming just to visit our natural habitats for the cheetah and to see, to have a glimpse of the cheetah.” said Ebtekar. “So we are working very seriously with international organizations as well as our national specialists and experts to protect this species.”

African cheetahs are also a threatened species, with an estimated 10,000 adults remaining.

While Iranian cheetahs “National Soccer Team” are running in the Brazil’s World Cup, the cheetahs in hyper arid landscapes of Iranian deserts are suffering from limited water availability due to presence of feral camels. There are two types of water resources within Iranian desert reserves, natural springs and artificial waterholes which are regularly filled with tanker by the rangers in hot summer. Camels can drink huge amount of water just at once and then they play and destroy basic infrastructure of waterholes, resulting in water flow on the ground. We plan to resolve the problem through intensive consultations we received from experienced local nomads, by constructing basic metal structure just around artificial resources to allocate these limited water reservoirs for the cheetahs and their prey. The camels still can meet their water needs from existing natural springs. Each reserve will cost around 1000 $ to ascertain camel-proof water resource and if you might be willing to support us to secure water for the cheetahs, please donate by click here.

[dt_button size=”medium” animation=”none” icon=”” icon_align=”center” color=”” link=”https://www.wildlife.ir/en/donate/” target_blank=”true”]Donate[/dt_button]

WITH A WORLD CUP DEBUT LOOMING, A RARE CHEETAH’S PLIGHT IS IN FOR SOME GLOBAL ATTENTION

When Iran’s football team takes to the field at this year’s World Cup competition in Brazil, it will sport on its jerseys not only its country’s insignia like all other teams, but also an image of the Asiatic cheetah emblazoned across the front. Allowing such an image is a radical departure for FIFA: its rules clearly stipulate that only country insignias and manufacturers’ logos can appear on jerseys. But it’s an even greater departure for Iran, whose top environment official requested this rare exception in a face-to-face meeting with FIFA’s head last year. Little more than a decade ago, few Iranians knew they were stewards of the last remaining Asiatic cheetahs on earth. Now, many hope the cheetahs’ international debut at the World Cup will raise global awareness and help them save their remnant population.

Centuries ago, Asiatic cheetahs roamed across much of the Middle East and into eastern India. Medieval royalty throughout the region often captured and trained cheetahs as hunting partners, even carrying them on horseback to hunting grounds. But somewhere along the way the hunters became the hunted. The last three cheetahs in India were shot by a Maharajah in 1947 when he spotted them in the beams of his car headlights. A growing human population and its livestock have crowded out Asiatic cheetahs in most countries, overgrazed the landscape, depleted their prey and often killed them on sight. By the 1990s, scientists estimated that Asiatic cheetahs were extinct in most of their former range and that fewer than 50 remained in Iran, holding out in the arid deserts in the eastern half of the country.

ICS supports current campaigns asking Iranian Ministry of Sports and Youth Affairs to display Asiatic cheetah as the national emblem on National Football team, during forthcoming Brazil championship games in 2014. As a leading conservation organization in the country, the ICS has been invited to be involved in the initiative which has been already shaped by Conservation of Asiatic Cheetah Project and Iran Department of Environment as well as some of the country’s environmentalists, started last month aiming to promote cheetah conservation inside the country. Accordingly, an official letter was submitted to the country’s Minister of Sports and Youth Affair on Sunday 27 October 2013 to highlight the movement. Signed by the ICS CEO, it is believed that indication of the Asiatic cheetah on the national football team clothes could highlight importance of the cheetah conservation at various social levels of the Iranian community”. “As one of the most critically endangered cats of the world which once ranges many parts of south and west Asia, presently the cheetah needs remarkable support”. Therefore, “the Iranian Cheetah Society (ICS) is honored to join the existing campaign established by various governmental and non-governmental organizations and activists as a substantial contribution to safeguard the Asiatic cheetahs in Iran”.

As you may remember, just a few weeks, a national conference was held in Iran by the Iranian Cheetah Society (ICS) in order to acknowledge tremendous efforts of 18 Cheetah Guardian working hardly to secure the cheetah ranges across Iran. While the event was quite successful to raise public attention through vast media coverage; however, another two persons were also highlighted in the ceremony which were actually lost in media. They were two herders, who lost their livestock to the cheetahs and the leopards in two different locations in the country. Mojtaba Ilkhani and Pourdel Nezhadravari, both witnessed the predators on their killed animals, but rather than trying to kill them using a shotgun or existing pesticide poisons, they immediately reported the case to Department of Environment game guard to inspect the situation. There is an established compensation program in Iran managed by the DoE; however, long bureaucratical process and financial constraints both have challenged its success.

Therefore, they were invited to the cheetah conference by the ICS to receive a remarkable financial incentive besides being acknowledged by the DoE’s head due to considering law. Furthermore, they are also invited to the ICS projects to share their expertise and to collaborate in field works aiming to protect the cheetahs in the country.

However, nobody can expect all local people to report their loss which sometimes can be substantial to their ivelihood whenever they encounter big cats. In recent years, a few cheetahs have been killed due to conflict cases. Therefore, while protecting of the reserves to sustain natural prey population can be essential to prevent conflict cases, but compensation programs need a crucial revision in Iran, if any conservation outcome is expected from allocating the money to losers. In the meantime, herders have high level of experience within the habitats, so their knowledge can be shared through involving them in conservation and monitoring efforts.

“If you are keen to see some stunning shots of the Asiatic cheetahs in extremely arid areas of Iran or massive Persian leopards in highlands, visit ICS on “youtube” to see these iconic species within their natural habitats in Iran. Besides monitoring Iran’s cats, the ICS is producing documentary films in order to spread the knowledge in the communities about the species and their survival. All these shots have been captured since 2011 using camera traps. You can see group life of the Asiatic cheetahs as well as their signing behavior together with Persian leopards. Also, educational clips are also added.